Child Custody in Brazil

Child Custody in Brazil

Updates

Updates

×

11 de maio de 2024

11 de maio de 2024

Child custody in Brazil is primarily governed by the Civil Code (Law No. 10.406/2002) and the Statute of the Child and Adolescent (Law No. 8.069/1990). According to Brazilian law, the child’s best interests principle is the primary consideration in determining child custody and support arrangements. These laws apply to all children living in Brazil, regardless of the nationality of their parents.

This article aims to provide a thorough understanding of child custody, particularly in cases involving foreign parents.

There are two main types of child custody in Brazil: physical custody and legal custody which are concepts substantially different from the understanding in place in many countries.

Physical custody refers to the parent with whom the child lives on a day-to-day basis. This means that the usual Parenting Plan that foresees a weekly division of physical custody only works in Brazil if both parents establish an exceptional format of custody (guarda alternada).

Legal custody refers to the parent who has the right to make decisions about the child’s upbringing, such as their education and healthcare.

Legal custody arrangements can be either joint or sole, depending on the circumstances and the best interests of the child according to the Court’s understanding.

In Joint custody, also known as “shared custody” both parents participate actively in the child’s life, including educational, medical, and social decisions, regardless of which parent has the physical custody of the children.

This is codified under Article 1.583 of the Brazilian Civil Code, which establishes that both parents are obliged to partake in the child’s life actively.

For example, if a child needs to be enrolled in a school, both parents should jointly decide which school is the best fit for the child. This cooperative approach also extends to medical decisions, such as choosing a healthcare provider or deciding on medical treatments.

Despite the concept of joint custody, it’s common in Brazil for the child to primarily reside with only one parent, that is referred as the primary custodian. In such arrangements, the other parent often has the right to be with the child every alternate weekend. This is generally the case regardless of the other parent’s legal right to participate in other aspects of the child’s life.

Even in joint custody arrangements, there are certain areas where the primary custodian can make unilateral decisions without consulting the father. For example, she may choose the child’s daily meals, clothing, and even minor healthcare decisions like taking over-the-counter medication for a common cold, without needing the father’s approval. Even if a foreign parent does not live in Brazil, they may still have joint custody rights to their child.

In most cases, Brazilian Courts tend to favor the granting of joint custody to both parents, emphasizing a balanced approach to parenting responsibilities, what can be granted even when one of the parents do not live in Brazil.

There was a common misconception that local courts typically favor mothers when awarding physical custody of children. However, this is not the case. The law does not explicitly give preference to either parent, and courts base their decisions exclusively on what serves the child’s best interests.

There are a number of factors that courts consider when making custody decisions, including the child’s relationship with each parent, the child’s age and developmental needs, the stability of each parent’s home environment, and each parent’s ability to provide for the child’s physical and emotional well-being.

While mothers may statistically be granted custody more often, this should not be interpreted as legal bias. Rather, it is a reflection of societal norms and specific case circumstances that may tilt the scales in favor of mothers.

For example, mothers are more likely to be the primary caregivers for children, and they may also have more flexible work schedules, been relevant to observe that, in recent years, Brazilian courts have increasingly adopted a balanced approach, awarding joint custody to both parents.

Sole custody is typically awarded in cases where one parent is adjudged unfit or incapable of fulfilling parental responsibilities effectively. In such situations, the non-custodial parent’s involvement is restricted to a supervisory role over the custodial parent’s decisions concerning the child, without the privilege of active participation in the child’s upbringing. This may be due to a variety of factors, such as substance abuse, domestic violence, or mental illness.

The legal process for determining child custody generally comprises two distinct phases. The first phase yields a provisional custody decision, serving as an immediate, temporary arrangement for the child’s care.

The court’s provisional decision is not final but aims to provide short-term stability for the child. It remains in effect until the court can make a comprehensive assessment based on gathered evidence, expert testimonies, and other relevant factors.

The second and final phase results in a definitive custody arrangement. Here, the court may either uphold or modify the provisional arrangement, guided by the principle of serving the child’s best interests.

If you need any further information about this topic, don’t hesitate to contact me.

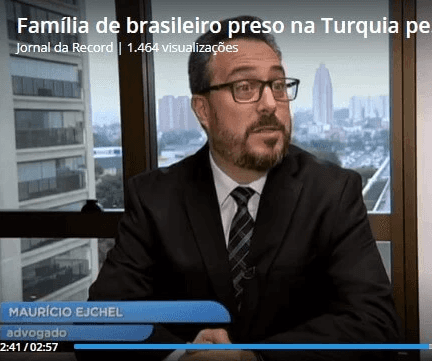

Dr. Mauricio Ejchel

Child custody in Brazil is primarily governed by the Civil Code (Law No. 10.406/2002) and the Statute of the Child and Adolescent (Law No. 8.069/1990). According to Brazilian law, the child’s best interests principle is the primary consideration in determining child custody and support arrangements. These laws apply to all children living in Brazil, regardless of the nationality of their parents.

This article aims to provide a thorough understanding of child custody, particularly in cases involving foreign parents.

There are two main types of child custody in Brazil: physical custody and legal custody which are concepts substantially different from the understanding in place in many countries.

Physical custody refers to the parent with whom the child lives on a day-to-day basis. This means that the usual Parenting Plan that foresees a weekly division of physical custody only works in Brazil if both parents establish an exceptional format of custody (guarda alternada).

Legal custody refers to the parent who has the right to make decisions about the child’s upbringing, such as their education and healthcare.

Legal custody arrangements can be either joint or sole, depending on the circumstances and the best interests of the child according to the Court’s understanding.

In Joint custody, also known as “shared custody” both parents participate actively in the child’s life, including educational, medical, and social decisions, regardless of which parent has the physical custody of the children.

This is codified under Article 1.583 of the Brazilian Civil Code, which establishes that both parents are obliged to partake in the child’s life actively.

For example, if a child needs to be enrolled in a school, both parents should jointly decide which school is the best fit for the child. This cooperative approach also extends to medical decisions, such as choosing a healthcare provider or deciding on medical treatments.

Despite the concept of joint custody, it’s common in Brazil for the child to primarily reside with only one parent, that is referred as the primary custodian. In such arrangements, the other parent often has the right to be with the child every alternate weekend. This is generally the case regardless of the other parent’s legal right to participate in other aspects of the child’s life.

Even in joint custody arrangements, there are certain areas where the primary custodian can make unilateral decisions without consulting the father. For example, she may choose the child’s daily meals, clothing, and even minor healthcare decisions like taking over-the-counter medication for a common cold, without needing the father’s approval. Even if a foreign parent does not live in Brazil, they may still have joint custody rights to their child.

In most cases, Brazilian Courts tend to favor the granting of joint custody to both parents, emphasizing a balanced approach to parenting responsibilities, what can be granted even when one of the parents do not live in Brazil.

There was a common misconception that local courts typically favor mothers when awarding physical custody of children. However, this is not the case. The law does not explicitly give preference to either parent, and courts base their decisions exclusively on what serves the child’s best interests.

There are a number of factors that courts consider when making custody decisions, including the child’s relationship with each parent, the child’s age and developmental needs, the stability of each parent’s home environment, and each parent’s ability to provide for the child’s physical and emotional well-being.

While mothers may statistically be granted custody more often, this should not be interpreted as legal bias. Rather, it is a reflection of societal norms and specific case circumstances that may tilt the scales in favor of mothers.

For example, mothers are more likely to be the primary caregivers for children, and they may also have more flexible work schedules, been relevant to observe that, in recent years, Brazilian courts have increasingly adopted a balanced approach, awarding joint custody to both parents.

Sole custody is typically awarded in cases where one parent is adjudged unfit or incapable of fulfilling parental responsibilities effectively. In such situations, the non-custodial parent’s involvement is restricted to a supervisory role over the custodial parent’s decisions concerning the child, without the privilege of active participation in the child’s upbringing. This may be due to a variety of factors, such as substance abuse, domestic violence, or mental illness.

The legal process for determining child custody generally comprises two distinct phases. The first phase yields a provisional custody decision, serving as an immediate, temporary arrangement for the child’s care.

The court’s provisional decision is not final but aims to provide short-term stability for the child. It remains in effect until the court can make a comprehensive assessment based on gathered evidence, expert testimonies, and other relevant factors.

The second and final phase results in a definitive custody arrangement. Here, the court may either uphold or modify the provisional arrangement, guided by the principle of serving the child’s best interests.

If you need any further information about this topic, don’t hesitate to contact me.

Dr. Mauricio Ejchel

Child custody in Brazil is primarily governed by the Civil Code (Law No. 10.406/2002) and the Statute of the Child and Adolescent (Law No. 8.069/1990). According to Brazilian law, the child’s best interests principle is the primary consideration in determining child custody and support arrangements. These laws apply to all children living in Brazil, regardless of the nationality of their parents.

This article aims to provide a thorough understanding of child custody, particularly in cases involving foreign parents.

There are two main types of child custody in Brazil: physical custody and legal custody which are concepts substantially different from the understanding in place in many countries.

Physical custody refers to the parent with whom the child lives on a day-to-day basis. This means that the usual Parenting Plan that foresees a weekly division of physical custody only works in Brazil if both parents establish an exceptional format of custody (guarda alternada).

Legal custody refers to the parent who has the right to make decisions about the child’s upbringing, such as their education and healthcare.

Legal custody arrangements can be either joint or sole, depending on the circumstances and the best interests of the child according to the Court’s understanding.

In Joint custody, also known as “shared custody” both parents participate actively in the child’s life, including educational, medical, and social decisions, regardless of which parent has the physical custody of the children.

This is codified under Article 1.583 of the Brazilian Civil Code, which establishes that both parents are obliged to partake in the child’s life actively.

For example, if a child needs to be enrolled in a school, both parents should jointly decide which school is the best fit for the child. This cooperative approach also extends to medical decisions, such as choosing a healthcare provider or deciding on medical treatments.

Despite the concept of joint custody, it’s common in Brazil for the child to primarily reside with only one parent, that is referred as the primary custodian. In such arrangements, the other parent often has the right to be with the child every alternate weekend. This is generally the case regardless of the other parent’s legal right to participate in other aspects of the child’s life.

Even in joint custody arrangements, there are certain areas where the primary custodian can make unilateral decisions without consulting the father. For example, she may choose the child’s daily meals, clothing, and even minor healthcare decisions like taking over-the-counter medication for a common cold, without needing the father’s approval. Even if a foreign parent does not live in Brazil, they may still have joint custody rights to their child.

In most cases, Brazilian Courts tend to favor the granting of joint custody to both parents, emphasizing a balanced approach to parenting responsibilities, what can be granted even when one of the parents do not live in Brazil.

There was a common misconception that local courts typically favor mothers when awarding physical custody of children. However, this is not the case. The law does not explicitly give preference to either parent, and courts base their decisions exclusively on what serves the child’s best interests.

There are a number of factors that courts consider when making custody decisions, including the child’s relationship with each parent, the child’s age and developmental needs, the stability of each parent’s home environment, and each parent’s ability to provide for the child’s physical and emotional well-being.

While mothers may statistically be granted custody more often, this should not be interpreted as legal bias. Rather, it is a reflection of societal norms and specific case circumstances that may tilt the scales in favor of mothers.

For example, mothers are more likely to be the primary caregivers for children, and they may also have more flexible work schedules, been relevant to observe that, in recent years, Brazilian courts have increasingly adopted a balanced approach, awarding joint custody to both parents.

Sole custody is typically awarded in cases where one parent is adjudged unfit or incapable of fulfilling parental responsibilities effectively. In such situations, the non-custodial parent’s involvement is restricted to a supervisory role over the custodial parent’s decisions concerning the child, without the privilege of active participation in the child’s upbringing. This may be due to a variety of factors, such as substance abuse, domestic violence, or mental illness.

The legal process for determining child custody generally comprises two distinct phases. The first phase yields a provisional custody decision, serving as an immediate, temporary arrangement for the child’s care.

The court’s provisional decision is not final but aims to provide short-term stability for the child. It remains in effect until the court can make a comprehensive assessment based on gathered evidence, expert testimonies, and other relevant factors.

The second and final phase results in a definitive custody arrangement. Here, the court may either uphold or modify the provisional arrangement, guided by the principle of serving the child’s best interests.

If you need any further information about this topic, don’t hesitate to contact me.

Dr. Mauricio Ejchel

Child custody in Brazil is primarily governed by the Civil Code (Law No. 10.406/2002) and the Statute of the Child and Adolescent (Law No. 8.069/1990). According to Brazilian law, the child’s best interests principle is the primary consideration in determining child custody and support arrangements. These laws apply to all children living in Brazil, regardless of the nationality of their parents.

This article aims to provide a thorough understanding of child custody, particularly in cases involving foreign parents.

There are two main types of child custody in Brazil: physical custody and legal custody which are concepts substantially different from the understanding in place in many countries.

Physical custody refers to the parent with whom the child lives on a day-to-day basis. This means that the usual Parenting Plan that foresees a weekly division of physical custody only works in Brazil if both parents establish an exceptional format of custody (guarda alternada).

Legal custody refers to the parent who has the right to make decisions about the child’s upbringing, such as their education and healthcare.

Legal custody arrangements can be either joint or sole, depending on the circumstances and the best interests of the child according to the Court’s understanding.

In Joint custody, also known as “shared custody” both parents participate actively in the child’s life, including educational, medical, and social decisions, regardless of which parent has the physical custody of the children.

This is codified under Article 1.583 of the Brazilian Civil Code, which establishes that both parents are obliged to partake in the child’s life actively.

For example, if a child needs to be enrolled in a school, both parents should jointly decide which school is the best fit for the child. This cooperative approach also extends to medical decisions, such as choosing a healthcare provider or deciding on medical treatments.

Despite the concept of joint custody, it’s common in Brazil for the child to primarily reside with only one parent, that is referred as the primary custodian. In such arrangements, the other parent often has the right to be with the child every alternate weekend. This is generally the case regardless of the other parent’s legal right to participate in other aspects of the child’s life.

Even in joint custody arrangements, there are certain areas where the primary custodian can make unilateral decisions without consulting the father. For example, she may choose the child’s daily meals, clothing, and even minor healthcare decisions like taking over-the-counter medication for a common cold, without needing the father’s approval. Even if a foreign parent does not live in Brazil, they may still have joint custody rights to their child.

In most cases, Brazilian Courts tend to favor the granting of joint custody to both parents, emphasizing a balanced approach to parenting responsibilities, what can be granted even when one of the parents do not live in Brazil.

There was a common misconception that local courts typically favor mothers when awarding physical custody of children. However, this is not the case. The law does not explicitly give preference to either parent, and courts base their decisions exclusively on what serves the child’s best interests.

There are a number of factors that courts consider when making custody decisions, including the child’s relationship with each parent, the child’s age and developmental needs, the stability of each parent’s home environment, and each parent’s ability to provide for the child’s physical and emotional well-being.

While mothers may statistically be granted custody more often, this should not be interpreted as legal bias. Rather, it is a reflection of societal norms and specific case circumstances that may tilt the scales in favor of mothers.

For example, mothers are more likely to be the primary caregivers for children, and they may also have more flexible work schedules, been relevant to observe that, in recent years, Brazilian courts have increasingly adopted a balanced approach, awarding joint custody to both parents.

Sole custody is typically awarded in cases where one parent is adjudged unfit or incapable of fulfilling parental responsibilities effectively. In such situations, the non-custodial parent’s involvement is restricted to a supervisory role over the custodial parent’s decisions concerning the child, without the privilege of active participation in the child’s upbringing. This may be due to a variety of factors, such as substance abuse, domestic violence, or mental illness.

The legal process for determining child custody generally comprises two distinct phases. The first phase yields a provisional custody decision, serving as an immediate, temporary arrangement for the child’s care.

The court’s provisional decision is not final but aims to provide short-term stability for the child. It remains in effect until the court can make a comprehensive assessment based on gathered evidence, expert testimonies, and other relevant factors.

The second and final phase results in a definitive custody arrangement. Here, the court may either uphold or modify the provisional arrangement, guided by the principle of serving the child’s best interests.

If you need any further information about this topic, don’t hesitate to contact me.

Dr. Mauricio Ejchel

Veja também

Father´s Rights in International Law

Updates

×

1 de nov. de 2024

Father´s Rights in International Law

Updates

×

1 de nov. de 2024

Father´s Rights in International Law

Updates

×

1 de nov. de 2024

How to Retain a Lawyer in Brazil

Updates

×

8 de abr. de 2024

How to Retain a Lawyer in Brazil

Updates

×

8 de abr. de 2024

How to Retain a Lawyer in Brazil

Updates

×

8 de abr. de 2024

Hague Child Abduction in Brazil

Updates

×

25 de nov. de 2023

Hague Child Abduction in Brazil

Updates

×

25 de nov. de 2023

Hague Child Abduction in Brazil

Updates

×

25 de nov. de 2023

Brazilian Law Manual

Updates

×

25 de out. de 2023

Brazilian Law Manual

Updates

×

25 de out. de 2023

Brazilian Law Manual

Updates

×

25 de out. de 2023

Father´s Rights in International Law

Updates

×

1 de nov. de 2024

How to Retain a Lawyer in Brazil

Updates

×

8 de abr. de 2024

Hague Child Abduction in Brazil

Updates

×

25 de nov. de 2023

Visite o Blog

Visite o Blog

MF. Ejchel International Advocacy. 1996

MF. Ejchel International

Advocacy

1996

MF. Ejchel International Advocacy.

1996

MF. Ejchel International Advocacy. 1996